Two First Ladies and the Post-Roe Future

In interviews 25 years apart, Betty Ford and Laura Bush both said they opposed overturning Roe v. Wade. The different reactions they received provide a window on where abortion politics may be headed.

In the summer of 1975, the 60 Minutes correspondent Morley Safer went to the White House for an interview with First Lady Betty Ford. Sitting down with Ford in the third floor solarium, Safer quickly sensed he was going to like the First Lady. “You can ask me anything you want and I’ll tell you the truth,” Ford told him. “I’m such a lousy liar if I tried to lie to you it would be transparent anyway.”

Ford did not disappoint, meeting a series of provocative questions from Safer with even-more provocative answers. “What are the pressures,” Safer asked, “on a woman living in this town?” It depends, said Mrs. Ford, on “the type of husband you have, whether he’s a wanderer or whether he’s a homebody.”

What about her own husband, President Gerald Ford? Had she ever worried he would stray? “I have perfect faith in my husband but I’m always glad to see him enjoy a pretty girl.”

When Safer asked about Ford’s teenage children and how they were navigating the changing mores of 1970s America, Ford allowed that “they’ve all probably tried marijuana.” Would she have smoked pot if it had been prevalent in her own youth? “Oh I’m sure I probably would.”

What would she do, Safer asked, if Ford’s daughter, Susan, then 18, came to her and said she was having “an affair” ( meaning premarital sex rather than infidelity.) “Well,” said Ford, “I wouldn’t be surprised. I think she’s a perfectly normal human being, like most girls.”

Two-and-a-half years earlier, in its Roe v. Wade decision, the Supreme Court had established a woman’s constitutional right to terminate a pregnancy. In the summer of 1975, male politicians in both parties were still fumbling their way toward a position on the abortion issue. Jerry Ford had said that he disagreed with Roe and that he opposed abortion in all but rare instances but that he did not favor amending the constitution to ban abortion nationwide. The whole topic seemed to make him uncomfortable.

But when Safer brought up the issue of abortion, Betty Ford didn’t even wait for the journalist to finish his question before offering an enthusiastic endorsement of the court’s action:

I feel very strongly that it was the best thing in the world when the Supreme Court voted to legalize abortion and, in my words, bring it out of the backwoods and put it in the hospitals where it belonged. I thought it was a great, great decision.

After 60 Minutes aired the interview, CBS was deluged with letters, “the biggest mail response we’ve ever had,” Safer would later say. Many wrote to express their indignation at the First Lady’s attitude toward sex and drugs. Newspapers filled whole pages with reader reactions to Ford’s comments about her daughter’s hypothetical “affair.”

But, half a century later, what’s most interesting about the episode is how little of the outraged response concerned the Republican First Lady’s position on abortion. While Ford’s thoughts about Roe did not entirely escape censure from the occasional letter writer, they received far less notice than did her comments about her children’s drug use and sexual experimentation. The New York Times covered Ford’s comments about her daughter’s affair at length but mentioned Ford’s abortion comments in a single sentence at the bottom of the piece.

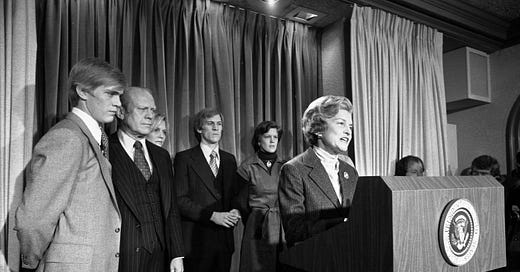

The Fords would remain in the White House for another year-and-a-half after Betty’s 60 Minutes interview. During that time, the First Lady reiterated her support for Roe multiple times, using the same enthusiastic and uncompromising language. Even at the 1976 Republican convention, where Jerry Ford faced lingering opposition from conservatives aligned with his barely-vanquished primary challenger, Ronald Reagan, Betty Ford did not moderate her tone. On the convention’s first night, she sat for an interview with reporters. The next day, newspapers ran a headline from the UPI: “Take Abortion ‘Out of Woods,’ Mrs. Ford Urges Convention.”

Twenty-five years later, in January 2001, incoming First Lady Laura Bush sat down for a round of interviews with female hosts of the network morning shows. In two days, her husband, George W. Bush, would be inaugurated as president. “I can’t wait until we’re on that inauguration platform,” Bush told the Today show’s Katie Couric.

But Bush’s trip to that platform was about to get a little bumpy, thanks to a question from Couric: Should abortion be legal in the United States?

Bush’s careful answer was artfully vague:

“I think we should do what we can to limit the number of abortions… and that is by talking about responsibility with girls and boys, by teaching abstinence, having abstinence classes everywhere in schools, in churches and in Sunday schools…”

She hadn’t answered Couric’s question. This was no surprise. Bush’s husband had won the Republican nomination in part thanks to the strong support of religious conservatives. An opponent of abortion rights, he spoke frequently on the campaign trail of his desire to create “a culture of life.” Reporters had long suspected that Laura Bush differed with her husband on the issue but no one had gotten her to admit as much in public.

Couric pressed further: “But having said that Mrs. Bush… even if you do advocate those things, do you believe women in this country should have a right to an abortion?”

Bush again tried to dodge: “I agree with my husband that we should try to reduce the number of abortions in our country by doing all those things.

Couric tried once more: “Should Roe v. Wade be overturned?”

Finally, Bush gave in. “No, I don’t think it should be overturned.”

Substantively, Bush had ended up in exactly the same place as Betty Ford 25 years before: breaking with their husbands to come out in favor of upholding Roe v. Wade. But tonally, the exchange bore little resemblance to Betty Ford’s fervent endorsement of abortion rights in her Morley Safer interview.

The reaction to her remarks was altogether different as well.

NBC’s plan had been to air the taped interview on the next morning’s Today show. In her recent memoir, Going There, Couric recalled how, as soon as the interview concluded, she called Tim Russert, NBC’s Washington Bureau Chief, to tell him she’d gotten Bush to acknowledge her support for Roe. “Katie, that’s huge, huge news,” said Russert. “We’ve got to get it on the Nightly News.”

Couric went on to describe the frenzy the interview caused:

Of course Tim was right; the First Lady’s comments blew up, creating a giant headache for the Bush administration. Pro-life groups anxiously reasserted the president-elect’s anti-abortion bona fides while Bush’s designated press secretary Ari Fleischer, repeatedly said he would not discuss ‘the personal view’ of the president-elect’s family…. Bush was steamed. When [NBC News President] Andy Lack greeted him after the inauguration, he jabbed Andy in the chest with his index finger and said, “I can’t believe that Katie Couric asked my wife about abortion!”

Laura Bush would not publicly discuss her views on abortion rights again until she and her husband had left Washington for good. “While cherishing life,” she wrote in her post-White House memoir, Spoken from the Heart, “I have always believed that abortion is a private decision, and there, no one can walk in anyone else’s shoes.”

Two pro-choice Republican First Ladies. Two very different ways of expressing an opinion on abortion rights.

How to explain the discrepancy? As high-level political spouses, Laura Bush and Betty Ford had a great deal in common. Both had devoted significant portions of their adult lives to the advancement of their husbands’ political careers. True, Ford was far more daring in interviews, more willing to break with her husband in public. But she believed in her husband’s long-term political objectives and was sensitive to his short-term needs. She was only going to devote herself to a cause if she was confident her advocacy would not cause major damage to the career of Jerry Ford.

So the fact that she felt comfortable speaking out in favor of abortion rights tells us something about the politic culture of the mid 1970s. Roe v. Wade was the law of the land but it had not yet taken a primary position in defining the two parties. There were pro-choice Republicans and pro-life Democrats; a pro-choice Republican First Lady could publicly break with her husband on the abortion issue without worrying that she would seriously jeopardize his political coalition.

By the time Laura Bush sat down with Katie Couric in 2001, the role of reproductive rights in the nation’s politics had been transformed. Culturally conservative Christians had become a dominant force in the Republican Party, the first and most crucial group of supporters a Republican president needed for any item on his agenda. They provided that support with the clear condition that that president would advance their number one objective, overturning Roe, by appointing pro-life jurists to the federal bench.

That meant that, even if she’d wanted to, Laura Bush didn’t have the luxury of giving an answer like Betty Ford’s. A Republican First Lady could afford to make a statement of strong support for upholding Roe in 1975. A Republican First Lady in 2001 could not.

That change tells us something important about what America might look like if, as expected, the Supreme Court overturns Roe later this month. In the weeks since the leak of Samuel Alito’s draft majority opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson, some commentators have suggested that we may be headed back to the pre-Roe United States. In a narrow sense, this is correct. As in the pre-Roe past, American women will not have a constitutionally protected right to terminate pregnancies but abortion will remain legal in some American states.

But in a larger sense, what’s coming in the post-Roe future will be entirely new. American women will not only be living in a country without federal abortion protections, they will be living in a country where one of the two major political parties is dominated by anti-abortion fervor. Today’s pro-life activists have made clear that, if the Court strikes down Roe, they will go on to pursue an agenda that would have been unthinkable to many Americans in the pre-Roe days. Some have set their sights on a nationwide abortion ban. Others are pushing states to curtail or even prohibit health-of-the-mother exceptions for abortion laws. In May, Oklahoma passed a bill that would prohibit abortions from the moment of fertilization. Louisiana even briefly considered legislative language that would hold mothers criminally liable in the event they received an abortion.

To think that these sorts of efforts can’t gain purchase is to ignore the central role that anti-abortion activists have assumed in one of the two major political parties in the five decades since Roe. We know what life looks like in a country in which these activists exert influence over the things that politicians and their spouses say on the topic of abortion rights. We are about to find out what it’s like when they control a great deal more.

This is First Rough Drafts, my free newsletter on how big events in history were covered at the time. Like this post? Feel free to share

Learn more about my new book, BECOMING FDR: The Personal Crisis that Made a President. Pre-order here.